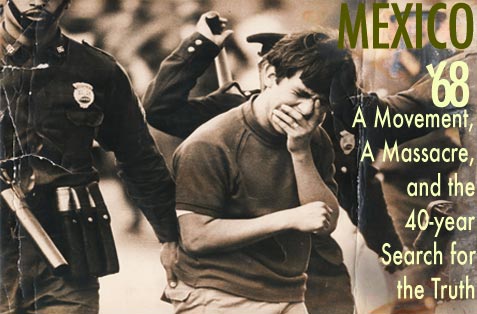

Photo courtesy Roberto Sánchez

In the summer of 1968, students in Mexico began to challenge the country's authoritarian government. But the movement was short-lived, lasting less than three months. It ended on October 2, 1968, ten days before the opening of the Olympics in Mexico City, when military troops opened fire on a peaceful student demonstration. The shooting lasted over two hours. The next day the government sent in cleaners to wash the blood from the plaza floor.

The official announcement was that four students were dead, but eyewitnesses said hundreds were killed. The death toll was not the only thing the government covered up about that event.

The Massacre of Tlatelolco has become a defining moment in Mexican history, but for forty years the truth of that day has remained hidden.

For decades, the official government history of October 2nd was that student snipers began firing on military troops, the army returned fire, and four students were killed. While the final death toll remains a mystery, documents discovered in recent years suggest that undercover military snipers were ordered to fire on their own troops in order to provoke the shooting of student demonstrators. Ten days before the opening of the Olympics in Mexico City, this was the government's strategy to put an end to the student movement.

Slide show of photographs of the student movement and massacre of 1968.

Archival footage recorded secretly by the government on the day of the massacre. Released nearly twenty years later, this footage helps support the theory that the shooting had been a provocation. In the video, armed gunmen shoot from the apartment buildings at the soldiers below. The gunmen were government officials dressed as civilians. They were ordered to fire on the soldiers, provoking them to shoot at students. Courtesy of Canal Seis de Julio and Secretaria de la Defensa Nacional (Sedena).

Official Mexican government document released after secret intelligence archives were opened for public scrutiny in the year 2000. This document was used as evidence to support the theory that the shooting was a provocation on the part of the government. It states that delegations and hospitals around Mexico City were reporting 26 people dead, including four women and one soldier, "the majority of which have not been identified…" The document also reports 100 people wounded and over one thousand detained. From Archivo General de la Nación, Galería 1, DFS Exp. 11-4, L. 44, F. 250-254. (In Spanish). PDF

FBI letter, Olympic Games, Mexico City, Mexico. October 12-27, 1968. The first government documents that helped uncover the mystery behind the Massacre on October 2nd were US declassified documents.This document discusses potential threats to the Olympic games, US citizens with histories of subversive activity, and anti-Castro Cubans who were expected to harass Cuban athletes during the games. Released in 1998 by the FBI, State Department and the CIA.

Other Resources:

The song, "Me Gustan los Estudiantes", was written in the early sixties by Chilean singer/songwriter/folkorist Violeta Parra (1917-1967). It became one of the anthems of the Mexican student movement, as well as of student movements all over Latin America. In the radio broadcast, the song is sung by Mercedes Sosa

Bios of interviewees for the radio documentary Mexico '68

Information about the government cover up and access Mexican secret intelligence documents

Blog about Mexico in 1968 (In Spanish)

Declassified documents about US involvement in Mexico.

Producers: Joe Richman and Anayansi Diaz-Cortes of Radio Diaries

Editors: Deborah George, Ben Shapiro

Executive Producer, NPR's All Things Considered: Chris Turpin

Production Assistants: Eric Pearse Chavez and Marco A. Morales

Website designer: Sue Johnson

Very Special Thanks to:

Samara Freemark, Posey Gruener, Julia Botero, Jacinto Rodríguez Munguía (Revista Eme Equis), Elaine Carey, Susana Zavala and Kate Doyle (National Security Archive), Nancy Ventura and Carlos Mendoza (Canal Seis de Julio), Raúl Alvarez Garín (Acervo Comité 68), Mónica Macisse, Felipe Morales and Carlos Hernández (Instituto Mora), José Gil Olmos and Jorge Carrasco (Revista Proceso), Margarita Castillo, José Buendía (Fundación Prensa y Democracia) Fernando Chamizo (Radio UNAM) and Cintia Velázquez (CCUT)

We also want to thank:

Marcelino Perelló and Janette Macari, Luis Almeida, Luis González de Alba, Emilio LegionV, Jaime Torres, Alejandra Gómez, Enriqueta Alarcón, Alejandra Zerecero, Mario Nuñez Mariel, Heidrun Holzfeind, Roberto Sánchez, Elena Poniatowska, Raúl Moreno Wonchee, Angeles Magdaleno, Juan Velázquez, José Reveles, Jaime Godded, Jorge Aguilar Mora, Raúl Habib, Ignacio Carrillo Prieto, Ernesto Carrión Soto, Nahum Calleros (CUEC), Lucy and Maricela Castillo

For the use of their archives or great insight, we are grateful to:

Canal Seis de Julio

Radio UNAM

Instituto Mora

Centro Cultural Tlatelolco, Memorial del 68

Acervo Comité 68

Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinemtagráficos

Archivo General de la Nación