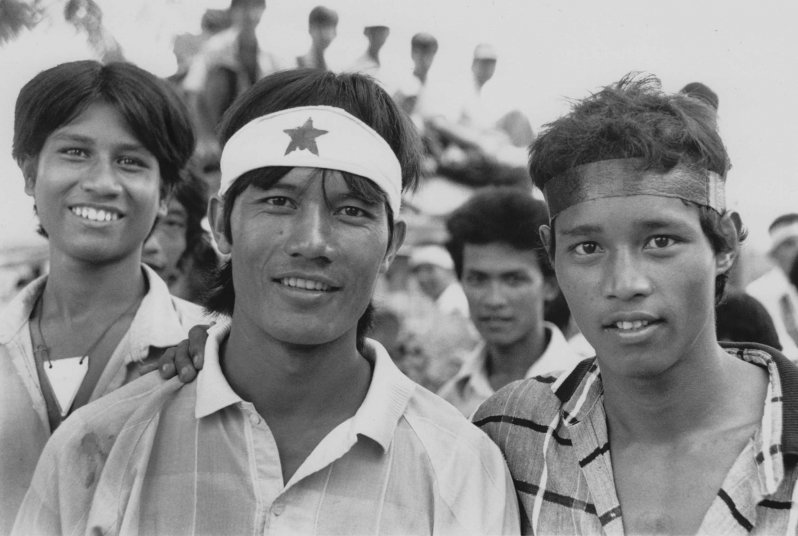

25 years ago, university students in Burma sparked a countrywide uprising. They called for a nationwide strike on 8/8/88, a date they chose for its numerological power.

They were attempting to overthrow the world’s longest running military dictatorship. The uprising ultimately failed, but it planted the seeds for the birth of democracy we are beginning to see in Burma. It was the moment Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, who became the icon of the democracy movement, first appeared on the political scene.

As the military government now loosens its grip on Burma, some are wondering if the country can really move forward if it fails to officially acknowledge what happened in 1988.

In this story, we take you back to the summer of 1988 in Burma, when the country seemed on the verge of dramatic change.

Approximately 3000 people died during the uprising of 1988, and another 3,000 were imprisoned by the regime.

The government has promised free and fair countrywide elections in 2015, and Aung San Suu Kyi is expected to run for president.

The voices of Burma ’88:

Htay Kywe was an archaeology student and a leader of the 1988 uprising. His interview with Christopher Gunness, carried on the BBC Burmese Service, announced the August 8 General Strike to the country. He spent 18 years in prison because of his activism. He lives in Yangon and is active in the 88 Generation civil society group.

Khin Ohmar was majoring in chemistry when she became involved in student demonstrations in March of 1988. Like many activists, she fled to Thailand following the military coup of September. She is the coordinator of the Burma Partnership, a democracy and human rights organization based in Mae Sot, Thailand.

Moethee Zun was a 1988 student leader and founder of the Democratic Party for a New Society political party. He spent much of the 90s on the Thai-Burma border, fighting alongside ethnic insurgent armies. He now lives in New York City. He was allowed back into Burma last year, and has travelled back to Yangon several times since then.

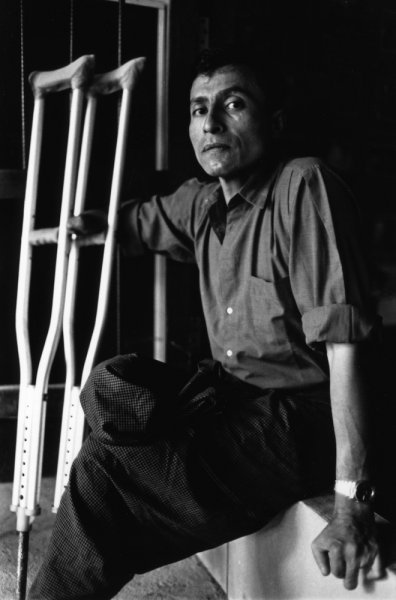

Myo Myint left the Burma Army in 1984 after losing an arm, a leg, and several fingers in a mortar attack. Be became a democracy and peace activist, and in 1988 focused on convincing soldiers to join the popular demonstrations. He was arrested for his activism and spent 15 years in prison. He lives in Indiana, and was the subject of the HBO documentary “Burma Soldier.”

In 1988, Nita May was an information officer for the British Embassy in Rangoon. She documented the uprising in that capacity, and later became active in Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy. She spent two years in prison for her political work. She lives in London and works for the BBC Burmese Service.

Burt Levin spent 30 years in Asia as a member of the U.S. Foreign Service, including three-and-a-half as the Ambassador to Burma. The U.S. had no one in that position from the time Levin left in 1990 until last year, when the post was restored to acknowledge reforms undertaken by the Myanmar government. Levin is currently a Visiting Professor of Asian Policy at Carleton College.

Christopher Gunness worked for the BBC for over 20 years beginning in the early 80s. He covered Asia from 1986 to 1989. His reporting on the 1988 uprising made his a household name in Burma, and he was blacklisted by the government until last year. He returned on August 6th for the first time since 1988.

This story was produced by Bruce Wallace, with Sarah Kate Kramer and Joe Richman of Radio Diaries, and edited by Deborah George and Ben Shapiro.

For more about Burma, listen to the 1-hour radio documentary, “New Year, New Burma,” produced by our colleagues Sherre DeLys and Francesca Panetta.